$25,253,505. That is the best estimate to date of how much money was paid by victims of ransomware attacks in the past two years in order to unlock their computer disks and get their data back. As a result, ransomware – malware that encrypts victims’ data and demands a payoff in exchange for the key to unlock the data – “has become one of the largest cybercrime revenue sources,” according to Google presenters at Black Hat USA 2017 conference in Las Vegas this week.

Participants in the study on “Tracking Ransomware End to End” included researchers from UC San Diego, New York University (NYU), and the blockchain analysis firm Chainalysis. (Blockchain is the public, decentralized ledger of transactions in Bitcoin, the cryptocurrency most widely used to settle ransomware demands.)

Rather than produce an academic paper first, the team opted to make a splash at the conference with a presentation to get the word out. The presenter: Google’s Kylie McRoberts. Now in its 20th year, Black Hat is the world’s leading information security event series.

Danny Yuxing Huang

The UC San Diego participant in the study, Computer Science and Engineering (CSE) Ph.D. candidate Danny Yuxing Huang, is also affiliated with the Center for Networked Systems (CNS). “We study the economics of operating ransomware: from maintaining infrastructure, generating revenue, to getting victims to pay,” noted Huang, adding that “our goals are to understand the business model of ransomware, and estimate their revenue and potential profitability.”

Huang tracked bitcoins that moved from potential victims to ransomware, and from ransomware to exchanges (as possible liquidation). “By masquerading as a part of the ransomware infrastructure,” explained Huang, “I also gathered statistics on infected computers, such as the number of infections over time, and the geographical distribution of infected machines.”

Damon McCoy, now a

professor at NYU,

participated in the study.

Google’s other university collaborator was Damon McCoy, a former postdoctoral scientist in CSE at UC San Diego from 2009 to 2011, who is now an assistant professor of computer science in NYU’s Tandon School of Engineering.

Together, the researchers investigated 300,000 files from 34 different types of ransomware and tracked payments on the blockchain to analyze the scale and the amount of money paid by victims.

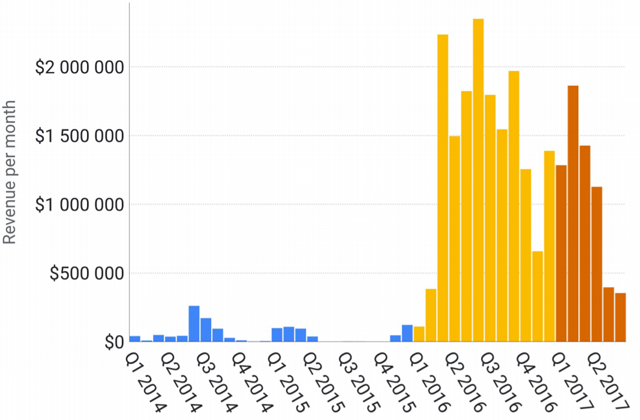

In the presentation, Google’s McRoberts reported that search queries for the term “ransomware” have increased by 877 percent since 2016, the first year when ransomware became a multi-million-dollar business (see chart).

business

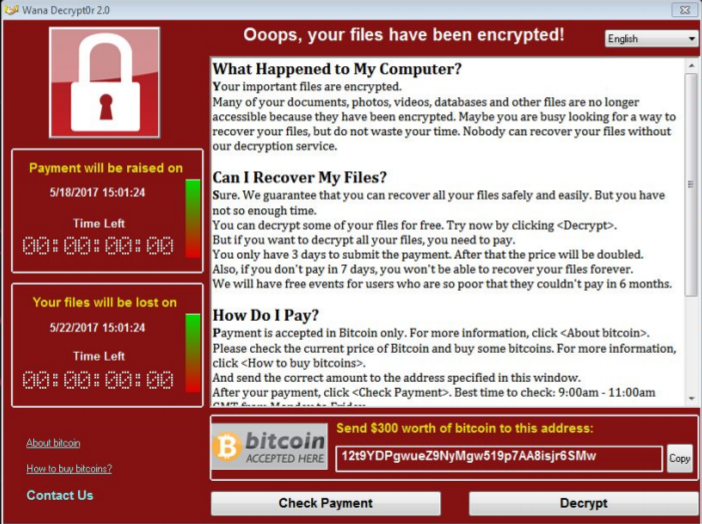

Of the $25 million in payments by Internet users to get their data back, some ransomware attacks generated more revenue than others. Only a fraction of the total was paid by victims of the widely publicized WannaCry ransomware in 2017, despite – or because of – the extensive damage it caused. Developed originally by the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA), WannaCry crippled hospitals (including Britain’s National Health Service), communications providers and some 10,000 other organizations as well as an estimated 200,000 individuals in more than 150 countries. Even so, payouts in response to WannaCry topped out at $140,000 – making it only the 11th-largest ransomware to date in terms of victim payouts. The Google presenter dubbed WannaCry an “impostor,” saying it should really be classified as “wipeware.” The study found that victims learned early on that the malware effectively wiped out the data because the software was unable to later unlock the victim’s computer even if the ransom was paid. The study noted that a variant on WannaCry called NotPetya was also wipeware, for the same reason, but also concluded that “wipeware pretending to be ransomware is on the rise.”

Less publicized ransom demands launched in 2016, on the other hand, generated far more income for the attackers than WannaCry, notably the Locky ($7.8 million to date) and Cerber ($6.9 million) ransomware attacks.

per month.

Locky was the first ransomware to make over $1 million per month. It has largely run its course, but left its mark on the criminal marketplace because it brought “ransoms to the masses”, according to the presentation at Blackhat USA. “Locky’s big advantage was the decoupling of the people who maintain the ransomware from the people who are infecting machines,” said NYU professor McCoy. “Locky just focused on building the malware and support infrastructure. Then they had other botnets spread and distribute the malware, which were much better at that end of the business.”

The same botnet that distributed Locky now also distributes Cerber and other ransomware built on Locky’s model. Cerber continues to rake in roughly $200,000 a month in ransom, as it has for more than a year, buoyed by its creation of an affiliate model that is “taking the world by storm,” noted Google.

According to the study, victims of all ransomware paid ransom by purchasing Bitcoins on at least 10 exchanges. The single largest market, LocalBitcoins.com, had 37% of the market in the two-year period.

The $25 million number in the new study reflects total ransomware payouts by victims. It is unclear, however, how much of the money made it back to the original authors of that ransomware.

UC San Diego contributor Danny Huang is nearing completion of his Ph.D. under advisors Alex Snoeren and research scientist Kirill Levchenko. The title of his dissertation is "Using Crypto-Curencies to Track Cyber Attacks, Speculative Investors and Human Traffickers." Huang is scheduled to mount the final defense of his dissertation at the end of August, and he'll be joining Princeton in the fall as a postdoctoral researcher.

Related Links

UC San Diego Economics of Ransomware Website

Presentation: Tracking Desktop Ransomware Payments (PDF)