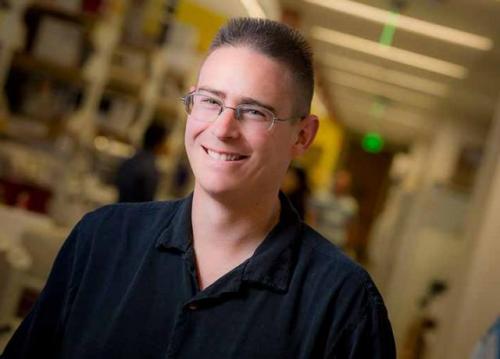

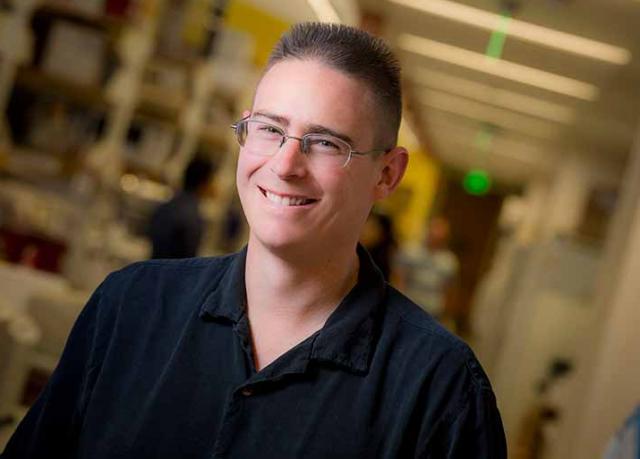

Our gut microbiomes — the varieties of microbes living in our digestive tracts — may play a role in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). “One of the really frustrating things about IBD in humans is that it’s hard to diagnose — it usually requires intestinal biopsies, which are not only imperfect, but invasive and expensive to collect,” said senior author Rob Knight, PhD, professor in the Departments of Pediatrics as well as Computer Science and Engineering, and director of the Center for Microbiome Innovation, all at UC San Diego.

Our gut microbiomes — the varieties of microbes living in our digestive tracts — may play a role in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). “One of the really frustrating things about IBD in humans is that it’s hard to diagnose — it usually requires intestinal biopsies, which are not only imperfect, but invasive and expensive to collect,” said senior author Rob Knight, PhD, professor in the Departments of Pediatrics as well as Computer Science and Engineering, and director of the Center for Microbiome Innovation, all at UC San Diego.

Since dogs can also suffer from IBD, researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine analyzed fecal samples from dogs with and without the disease. They discovered a pattern of microbes indicative of IBD in dogs. With more than 90 percent accuracy, the team was able to use that information to predict which dogs had IBD and which did not. However, they also determined that the gut microbiomes of dogs and humans are not similar enough to use dogs as animal models for humans with this disease.

The study is published October 3 in Nature Microbiology.

According to Knight, most people with IBD have similar changes in the types of microbes living in their intestinal tracts, relative to healthy people. Yet it’s still difficult to discern healthy people from those with IBD just by looking at the microbes in their fecal samples. In addition, Knight said it’s not yet clear whether the microbial patterns associated with IBD contribute to the disease’s cause or are a result of the disease.

In a separate line of study, pets appear to be a conduit for microbe sharing in a house. Knight and collaborators previously found that microbial communities on adult skin are on average more similar to those of their own dogs than to other dogs. With a fair amount of precision, they can pick your dog out of a crowd based solely on overlap in your microbiomes.

Read the full UC San Diego news release.

Nature Microbiology Article