Underwater robots developed by researchers at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography with the involvement of faculty from the Computer Science and Engineering department as well as Calit2's Qualcomm Institute (QI) are offering scientists an extraordinary new tool to study ocean currents and the tiny creatures they transport. Swarms of these underwater robots are already answering some basic questions about the most abundant life forms in the ocean — plankton.

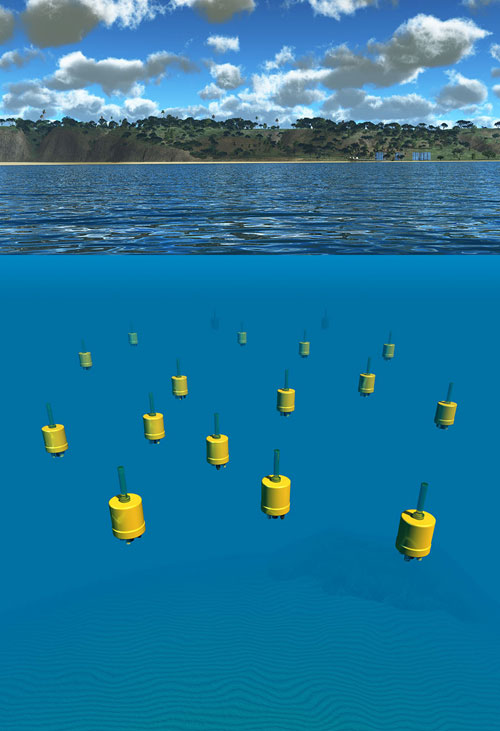

off the coast of Del Mar. Image courtesy the Jaffe

Lab for Underwater Imaging/Scripps Oceanography

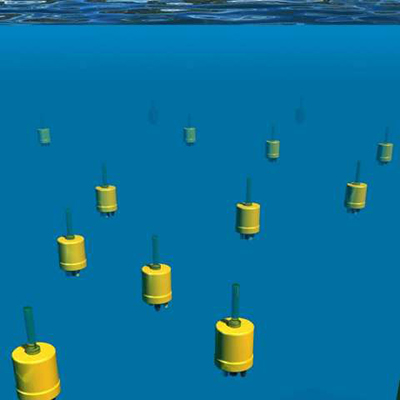

Scripps research oceanographer Jules Jaffe designed and built the miniature autonomous underwater explorers, or M-AUEs, to study small-scale environmental processes taking place in the ocean. The ocean-probing instruments are equipped with temperature and other sensors to measure the surrounding ocean conditions while the robots “swim” up and down to maintain a constant depth by adjusting their buoyancy. The M-AUEs could potentially be deployed in swarms of hundreds to thousands to capture a three-dimensional view of the interactions between ocean currents and marine life.

For a study published in the Jan. 24 issue of the journal Nature Communications, Jaffe and Scripps biological oceanographer Peter Franks deployed a swarm of 16 grapefruit-sized underwater robots programmed to mimic the underwater swimming behavior of plankton, the microscopic organisms that drift with the ocean currents. The study’s coauthors include CSE Prof. Ryan Kastner; CSE lecturer and postdoctoral researcher Diba Mirza; QI principal development engineer Curt Schurgers; as well as Scripps engineer Paul Roberts and student intern Adrien Boch.

The research study was designed to test theories about how plankton form dense patches under the ocean surface, which often later reveal themselves at the surface as red tides. “These patches might work like planktonic singles bars,” said Franks, who has long suspected that the dense aggregations could aid feeding, reproduction, and protection from predators.

Two decades ago Franks published a mathematical theory predicting that swimming plankton would form dense patches when pushed around by internal waves—giant, slow-moving waves below the ocean surface. Testing his theory would require tracking the movements of individual plankton—each smaller than a grain of rice—as they swam in the ocean, which is not possible using available technology.

Jaffe instead invented “robotic plankton” that drift with the ocean currents, but are programmed to move up and down by adjusting their buoyancy, imitating the movements of plankton. A swarm of these robotic plankton was the ideal tool to finally put Franks’ mathematical theory to the test.

“The big engineering breakthroughs were to make the M-AUEs small, inexpensive, and able to be tracked continuously underwater,” said Jaffe. The low cost allowed Jaffe and his team to build a small army of the robots that could be deployed in a swarm.

co-authored the swarm study led by Scripps

Institution of Oceanography scientists.

The researchers in CSE and the Qualcomm Institute developed acoustic signaling techniques to track submerged M-AUE vehicles (required because GPS global positioning does not work underwater). The resulting algorithms generated a best estimate of the position of each vehicle over time, merging a variety of heterogeneous system inputs and constraints, while overcoming challenges such as non-concurrent arrivals of the signaling messages and clock uncertainties. "The system was designed to have vehicles mimic the motion of parcels of water, so we could learn about the associated ocean phenomena," noted QI's Schurgers. "Figuring out and recording these positions was therefore one of the key components."

During a five-hour experiment, the Scripps researchers along with their UC San Diego colleagues deployed a 300-meter (984-foot) diameter swarm of 16 M-AUEs programmed to stay 10 meters (33 feet) below the ocean's surface off the coast of Torrey Pines, near La Jolla, Calif. The M-AUEs constantly adjusted their buoyancy to move vertically against the currents created by the internal waves. The three-dimensional location information collected every 12 seconds revealed where this robotic swarm moved below the ocean surface.

(M-AUEs) that make up the underwater swarms.

The results of the study were nearly identical to what Franks predicted. The surrounding ocean temperatures fluctuated as the internal waves passed through the M-AUE swarm. And, as predicted by Franks, the M-AUE location data showed that the swarm formed a tightly packed patch in the warm waters of the internal wave troughs, but dispersed over the wave crests.

“This is the first time such a mechanism has been tested underwater,” said Franks.

The experiment helped the researchers confirm that free-floating plankton can use the physical dynamics of the ocean—in this case, internal waves—to increase their concentrations to congregate into swarms to fulfill their fundamental life needs. “This swarm-sensing approach opens up a whole new realm of ocean exploration,” said Jaffe. Augmenting the M-AUEs with cameras would allow the photographic mapping of coral habitats, or “plankton selfies,” according to Jaffe.

Related Links

Read the full news release on the Scripps Institution of Oceanography website.